Dred Scott v. Sandford and John Brown’s Raid: Catalysts of the Civil War

The years leading to the American Civil War witnessed two transformative events that reshaped the nation’s political and social structure. The Supreme Court’s Dred Scott decision of 1857 fundamentally changed the legal status of African Americans and the federal government’s authority over slavery in U.S. territories. This ruling marked a critical turning point in American jurisprudence, establishing precedents that would require constitutional amendments to overturn. The aftermath of this decision reverberated through American society, intensifying the growing discord between North and South.

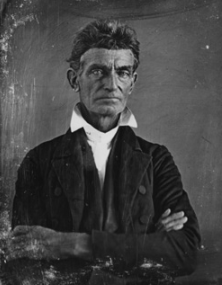

Two years after the Dred Scott decision, John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry in 1859 brought the nation’s tensions to a boiling point. Brown, an ardent abolitionist, led twenty-one men in an attempt to seize the federal arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, Virginia, planning to arm enslaved people and trigger a larger uprising. Though the raid failed militarily, its impact on American society proved profound, transforming Brown into a martyr for the abolitionist cause while confirming Southern fears about Northern intentions.

For educators seeking to teach these critical historical events, Sooner Standards offers engaging resources</a> that help students understand these complex topics. Their materials break down these significant events into accessible lessons, enabling students to grasp how these watershed moments contributed to the outbreak of the Civil War.

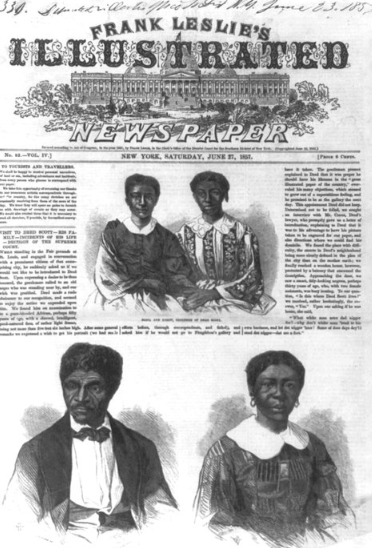

The Legal Journey of Dred Scott

Dred Scott’s path through the American legal system began in 1846 when he filed a lawsuit for his freedom in St. Louis Circuit Court. Scott based his claim on his previous residence in free territories, where his owner, Dr. John Emerson, had taken him. The principle of “once free, always free” had precedent in Missouri courts, giving Scott’s initial case strong legal standing. This first step in his legal journey would eventually lead to one of the most significant Supreme Court decisions in American history.

The Missouri Supreme Court reversed the initial ruling in Scott’s favor, prompting his legal team to take the case to federal court. This transition transformed the case from a straightforward freedom suit into a constitutional battle about citizenship and federal authority. The federal case centered on whether courts had jurisdiction to hear Scott’s claim, which required determining if African Americans could be citizens of the United States.

Chief Justice Roger B. Taney’s majority opinion systematically addressed each constitutional question presented in the case. His interpretation of the Constitution’s original intent led him to conclude that the framers never intended African Americans to be citizens. This sweeping decision went far beyond dismissing Scott’s case, fundamentally altering the legal status of all African Americans in the United States.

The Impact of the Dred Scott Decision

The Supreme Court’s ruling immediately nullified existing state personal liberty laws, which many Northern states had enacted to protect free blacks and runaway slaves. These laws had provided legal safeguards, including the right to trial by jury for accused fugitive slaves and prohibitions against state officials assisting in capturing runaway slaves. The Court’s decision effectively stripped away these protections.

State courts faced new requirements in handling cases involving enslaved people. The decision established that state courts must recognize slaves as property even if slavery was illegal in their state. This requirement created complex legal situations in free states, where courts now had to balance their state constitutions’ anti-slavery provisions against the federal requirement to recognize slave property rights.

The ruling transformed newspaper coverage and public discourse about slavery. Northern newspapers became more critical of the Supreme Court and more willing to publish anti-slavery content. Southern papers used the decision to justify their position that slavery was a permanent and protected institution. This media polarization contributed to the growing communication gap between North and South.

John Brown’s Path to Radicalization

John Brown’s journey toward armed resistance began during his early experiences with the Underground Railroad. His father’s involvement in helping escaped slaves exposed young Brown to slavery’s human cost, shaping his understanding of the system’s impact on families. These early experiences watching frightened families seeking safety made a lasting impression on Brown, strengthening his determination to fight against slavery.

The passage of the Fugitive Slave Act in 1850 marked a turning point in Brown’s approach to abolition. This law required Northern states to return escaped slaves, convincing Brown that the government had become a tool of slave owners. His growing belief that peaceful resistance would prove ineffective led him to consider more direct methods of opposing slavery.

Brown’s experiences in Kansas Territory during the mid-1850s further radicalized his methods. The conflict over whether Kansas would enter the Union as a free or slave state erupted into violence, with pro-slavery forces attacking anti-slavery settlers. Brown’s response to these attacks, including his role in the Pottawatomie Creek killings, demonstrated his willingness to use force to combat slavery.

Planning the Harper’s Ferry Raid

Brown selected Harper’s Ferry as his target because of its strategic value and symbolic importance. The federal arsenal stored approximately 100,000 weapons and significant ammunition supplies. The town’s position near the Potomac and Shenandoah Rivers would provide escape routes, while its proximity to the Appalachian Mountains offered potential hiding places.

The preparation phase involved gathering support from Northern abolitionists known as the “Secret Six.” These supporters included Thomas Wentworth Higginson, Samuel Gridley Howe, Theodore Parker, Franklin Benjamin Sanborn, Gerrit Smith, and George Luther Stearns. They provided Brown with money, weapons, and other resources essential for the raid.

Brown established a temporary base at Kennedy Farm in Maryland, four miles from Harper’s Ferry, under the alias Isaac Smith. This location served as a staging area where his men could gather without attracting attention. He studied the arsenal’s security patterns and developed a timeline for the attack, planning to seize the armory, take hostages from prominent local families, and distribute weapons to slaves who would join the uprising.

The Raid’s Execution and Military Response

The raid began on the night of October 16, 1859, when Brown led his force of 21 men toward Harper’s Ferry. They first captured the watchman at the Potomac River bridge, establishing control over this critical crossing point. The group then seized the federal armory and arsenal without firing a shot, catching the night watchman by surprise.

The situation changed dramatically when a Baltimore & Ohio train approached the town around 1:00 a.m. Brown’s men stopped the train, and during this delay, the baggage master was killed when he refused to obey their commands. This shooting proved to be a tactical error, as Brown allowed the train to continue its journey after an hours-long delay, enabling it to alert authorities about the raid.

President James Buchanan ordered a detachment of U.S. Marines to Harper’s Ferry under the command of Colonel Robert E. Lee. The Marines arrived early on October 18, joining local militia forces that had surrounded the engine house where Brown and his surviving men held their remaining hostages. The final assault lasted only minutes, with Brown wounded and captured.

Trial and Legacy

Virginia authorities moved quickly to try Brown for treason, inciting slave rebellion, and murder. The trial opened on October 27, 1859, just ten days after his capture. Brown’s behavior during the proceedings transformed the trial into a public platform for his anti-slavery views, with his powerful final statement resonating across the nation.

The weeks between Brown’s sentencing and execution saw intense national debate about his actions and character. Northern abolitionists praised his moral courage while condemning his violent methods. Southern leaders viewed him as a dangerous revolutionary who threatened their society’s foundations. His composed demeanor during imprisonment impressed even some opponents.

Brown’s execution on December 2, 1859, triggered dramatically different reactions across the nation. Church bells tolled in many Northern cities, while celebration dominated Southern responses. His death elevated him to martyr status among abolitionists and intensified the moral debate over slavery. These divergent reactions deepened the sectional divide and accelerated the nation’s movement toward civil war.

Summary

The Dred Scott decision and John Brown’s raid stand as defining moments in American history that accelerated the nation’s path toward civil war. The Supreme Court’s ruling stripped citizenship rights from African Americans and protected slavery in federal territories, while Brown’s failed raid intensified fears and divisions between North and South. These events transformed the national dialogue about slavery from a political dispute into a moral crisis that peaceful compromise could no longer resolve.

The legal implications of the Dred Scott case persisted until the passage of the 13th and 14th Amendments, while the symbolic power of Brown’s raid continued to influence American social movements long after his execution. Together, these events demonstrate how legal decisions and direct action can catalyze profound social change, even when their immediate objectives fail.

Understanding these historical events remains crucial for modern students and citizens. They illustrate how institutional decisions and individual actions can shape national destiny, while highlighting the complex relationship between law, morality, and social change in American society.

Teachers pay Teachers: Dred Scott to Harper’s Ferry: Critical Turning Points of the Civil War (Complete Unit)